My last column addressed a survey I conducted to see how aquatics facilities handle lightning storms and help ensure the safety of visitors and staff.

I wanted to see how much practices had changed in the last couple decades. Not much, as it turns out. I also found a lack of consensus on how to proceed when lightning is imminent, among both indoor and outdoor facilities.

Survey results confirmed that while the vast majority of outdoor pools do close during thunderstorms (98%), they vary in timing and duration of the closure, and instructions given to swimmers.

This probably stems from inconsistent approaches and messaging on the subject from national organizations, both inside and outside the aquatics world. Here, we examine these inconsistencies. Plus, we’ll look at some troubling shortcomings indicated by the survey.

Navigating the contradictions

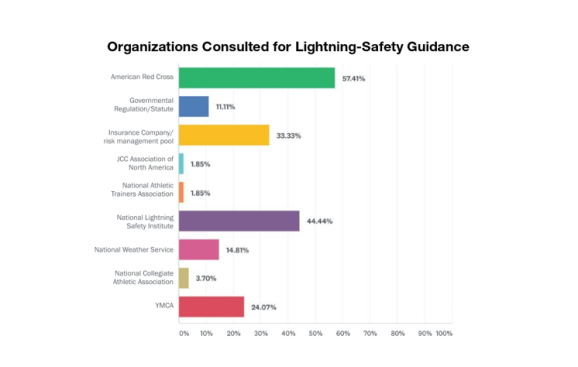

It’s no wonder that practices varied from facility to facility. Of those surveyed, 80% said they follow the recommendations of a chosen safety organization. When you look at the advice given by these groups, the lack of consensus becomes very clear.

As part of my research, I examined available literature to see if these organizations communicate a consistent message to facility operators. I found industry agreement that people should not swim outdoors during a thunderstorm. However, no standard message as to when exactly to close the pool was identified. Recommendations on when to suspend activities varied by organization, with some appearing to contradict themselves.

Let’s start with common practice. When discussing how to manage lightning risks, most cite the “Flash to Bang” rule, in which the operator counts the seconds from the first flash of lightning to the first sound of thunder. According to this rule, you can estimate proximity of the storm in miles by dividing the seconds by five. Therefore, people should seek shelter when the time from flash to bang is 30 seconds or less, as that indicates the storm is about 6 miles or less away.

Shawn DeRosa

But this approach doesn’t align with organizations that specialize in lightning and weather events. For instance, the National Weather Service takes a more conservative approach, stating, “When Thunder Roars, Go Indoors.” According to NWS, “[If] you hear thunder, lightning is close enough to strike …” It says everyone should move to safe shelter immediately upon hearing thunder, and stay put at least 30 minutes after hearing the last strike. There is no counting seconds — any sound of thunder requires immediate evacuation.

The American Meteorological Society (AMS) takes an even more conservative approach: “If the skies start to look threatening or you hear thunder, go inside a safe place immediately.”

If anything, the oft-cited National Lightning Safety Institute muddies the waters more, even contradicting its own recommendations. On one hand, NLSI recommends the standard Flash to Bang approach. But in a follow-up statement and clarification, NLSI president/CEO Richard Kithil stated, “At the first signs of thunder or lightning, all pool activities should be suspended (showers, too) until 30 minutes after the last observed thunder or lightning.” So it simultaneously recommends Flash to Bang and the NWS guideline.

Search for answers

This leaves operators to wonder: Which is it? Is it safe to count seconds from flash to bang, or should we move indoors immediately, assuming that audible thunder indicates we are within striking distance?

Definitive answers are not found in the sports, academic or aquatics fields. The NCAA requires institutions to develop a lightning safety plan, designate a weather watcher, and monitor local conditions. Beyond that, its guidelines appear to conflict with those of other groups. For example, Guideline 1E states: “Lightning safety experts suggest that if you hear thunder, begin preparation for evacuation; if you see lightning, consider suspending activities and heading for your designated safer locations.” This provides less specificity, not more, and seems to contradict other organizations.

The National Athletic Trainer’s Association (NATA) is more conservative, stating, “If thunder can be heard, lightning is close enough to be a hazard, and people should go to a safe location immediately.” NATA recommends that event organizers “postpone or suspend activities if a thunderstorm appears imminent before or during activity [emphasis added].” This places athletic trainers working at collegiate facilities in a difficult situation, as their association advises one approach, whereas the NCAA advises another.

While the American Red Cross falls in line with more conservative groups, its Advisory Council on First Aid, Aquatics, Safety and Preparedness determined that existing lightning safety recommendations regarding swimming pools were supported mostly by expert opinion and logical conjecture rather than convincing scientific evidence.

The Red Cross states: “Due to the potentially severe consequences of being struck by lightning, it is logical from safety, ethical and legal perspectives to abide by the existing lightning safety recommendations, because there is no evidence to suggest that they endanger persons and in fact may save lives and prevent injuries.” Ultimately, however, the Red Cross concedes that this is not a standard or a guideline but rather a conservative option to manage the risk.

Unsafe practices

Clearly, the industry needs more concrete guidelines about lightning safety in aquatics facilities.

Shawn Derosa

Some troubling findings in my survey bring this into more stark relief, showing where operators may inadvertently place staff and clients at risk.

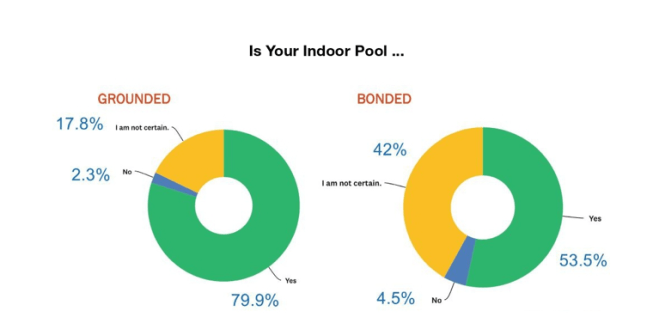

For instance, bonding and grounding comprise two of the most basic and important precautions against electrical hazards. Bonding involves joining the metal components of the pool and space together to form a pathway for stray current to migrate without placing individuals at risk. In its simplest of terms, grounding is the act of connecting bonded parts to earth to prevent the buildup of voltages that may result in undue hazards to connected equipment or people.

Of survey takers, between 42% (indoor) and 48% (outdoor) did not know if their pools were bonded. Between 18% (indoor) and 23% (outdoor) could not say if their pools were grounded.

Charts courtesy Shawn DeRosa

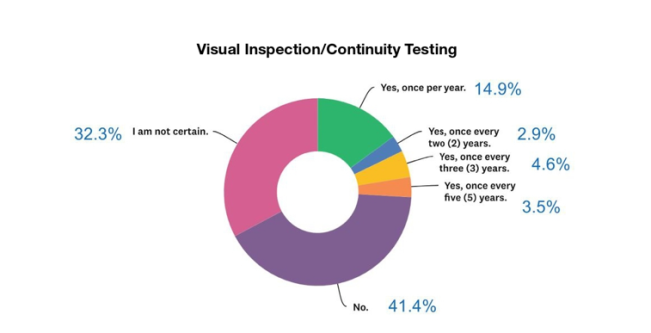

When asked whether their pools must undergo regular electrical inspections such as visual and continuity testing, nearly one-third of both indoor and outdoor operators did not know. Approximately 25% indicated that regular electrical inspections were required, whereas approximately 40% said they were not. About 60% couldn’t indicate when the last electrical inspection occurred.

Participants also were asked whether their organizations instituted policies or procedures that restrict telephone or computer use during electrical events. Over the years there have been documented lightning-related fatalities to persons talking on a corded phone (including a cell phone that was plugged in and charging) or while using a computer plugged into an outlet. Because of this, the NWS recommends people stay off corded phones, computers and other electrical equipment that makes direct contact with electricity.

Despite this cautionary advice, 90% of survey respondents indicated that there was no restriction on computer or telephone use at their place of employment during electrical storms.

Improving on history

Survey results suggest that it may be time for pool operators to dust off their lightning plans to ensure that current policies and procedures are consistent with best practices in the industry.

The next installment will discuss how.