When scanning a pool, it isn’t readily apparent which guests have autism. But sensitivity to the issue often will reveal when a child has a cognitive impairment. The following vignettes illustrate how lifeguards should respond to particular situations when it’s learned that autism is a factor.

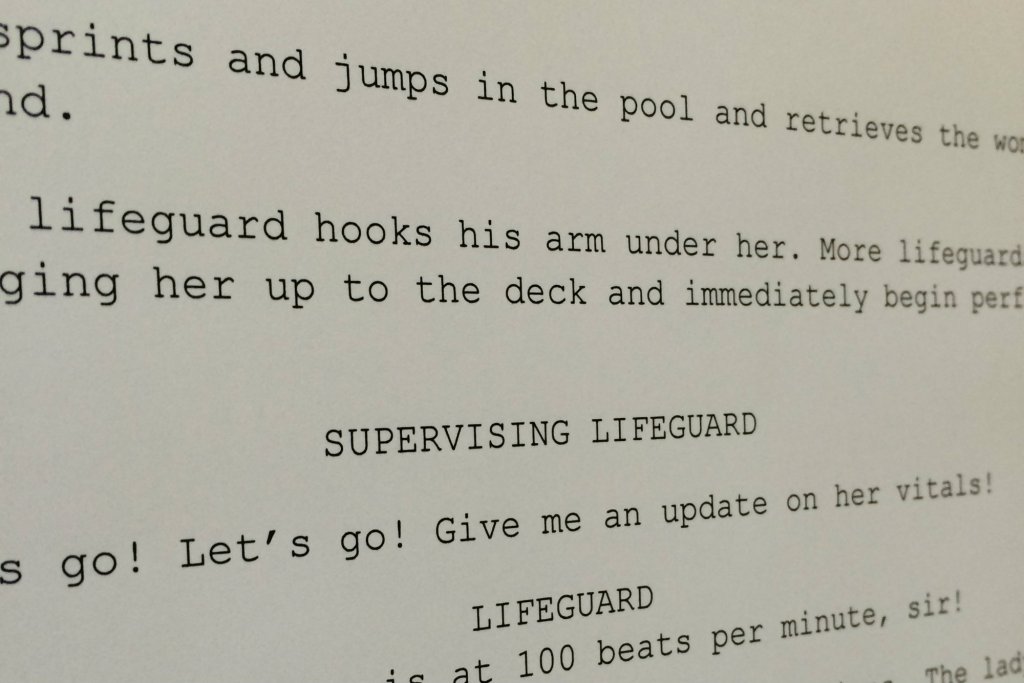

Scene: Imagine you’re approached by a parent saying his or her child has gone missing in the waterpark and has ASD. To find the youngster as quickly as possible, a lifeguard should ask two critical questions:

Why it works: Asking about the child’s communication skills (or lack thereof) cuts right to the chase. “This instantly saves time,” says Mike Pastor, training manager at Legoland California Resort. (The Carlsbad theme- and waterpark routinely trains personnel how to effectively interact with people who have cognitive disorders.) It’s a cue that the lifeguard already understands autism, sparing the parent from wasting precious time explaining the child’s condition. Plus, the guard will know how to communicate with the child once he or she is found. “If they’re nonverbal, it’s important to know that they’re not ignoring you,” advises Gary Weitzen, executive director of Brick, N.J.-based Parents of Autistic Children. “He just doesn’t have the physical ability to respond verbally.”

The second question is equally important: Some children with ASD are fascinated by certain attractions, so the answer may point you in the right direction. For example, Legoland’s big rotating pirate ship, Captain Cranky’s Challenge, can mesmerize some. “We’ll often ask that question and they’ll say, ‘Yeah, they love the boat ride.’ And, sure enough, the child is right there,” Pastor says.

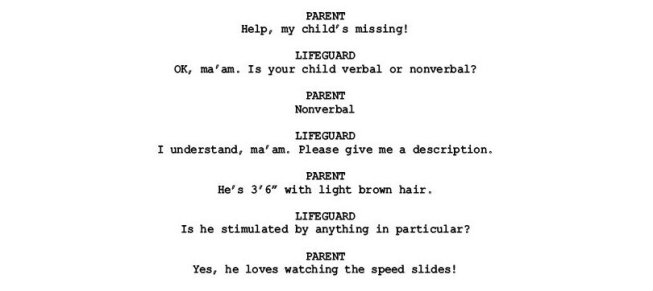

Scene: A guest is having a meltdown. A lifeguard responding to this situation needs to be tactful.

Why it works: Why it works: Becoming involved in a parental matter might go against a lifeguard’s instinct. But by offering a helping hand, you help curb another potential cause of escalation — intervention from other customers. Parents will commonly explain that the child has autism, which is the guard’s cue to point out quiet areas and baby-care stations and discuss the assisted access pass, Pastor says.

Weitzen concurs: “Parents just want to hear, ‘What do you need?’” In some cases, they’ll respond by asking the guard to keep crowds back to give the child space.

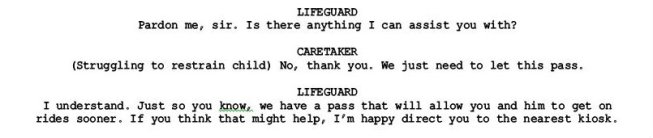

Scene: A child with autism isn’t responding to the lifeguard’s orders. It’s likely the kid isn’t being belligerent — perhaps the guard just isn’t making any sense.

Why it works: Some children with autism tend to interpret things literally, so figurative phrases such as “slow it down” would only confuse them. “What is ‘it’ and how do I slow it ‘down’?” the child might wonder. That’s why Weitzen advises using concrete language and avoiding figures of speech. There’s little room for interpretation in “stop running around the pool.” That’s something you could illustrate on a piece of paper if you had to.

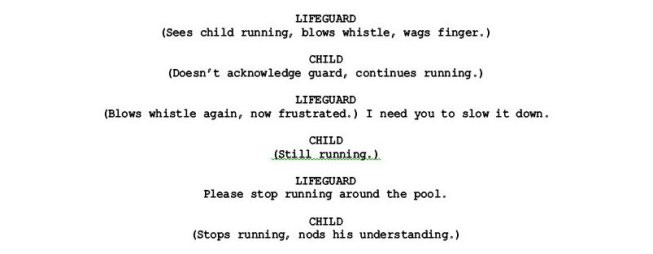

Scene: A guest needs medical attention. Some children with autism are averse to touch, so it helps if the lifeguard gives them options.

Why it works: You’re not asking “May I?” If the child says no, you’re in a predicament. That’s why it’s important to give the guest some say in the medical proceedings. “Something as simple as that puts a little power back in the child’s realm,” Weitzen says. If, however, this was an emergency situation, “do what you need to do, the way you’ve been trained.”

-

Autism at the Waterpark

For waterparks, meeting special needs without alienating non-disabled guests can be puzzling. Here's how to piece together a policy that works

-

Sam’s Club: Here’s How One Watepark Creates Exclusive, VIP Events for Guests with Special Needs

On select evenings, Sahara Sam's Oasis becomes the go-to destination for families living with disabilities